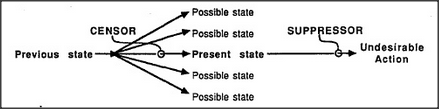

To see what suppressors and censors have to do, we must consider not only the mental states that actually occur, but others that might occur under slightly different circumstances.

Suppressors work by interceding to prevent actions just before they would be performed. This leads to a certain loss of time, because nothing can be done until acceptable alternatives can be found. Censors avoid this waste of time by interceding earlier. Instead of waiting until an action is about to occur, and then shutting it off, a censor operates earlier, when there still remains time to select alternatives. Then, instead of blocking the course of thought, the censor can merely deflect it into an acceptable direction. Accordingly, no time is lost.

Clearly, censors can be more efficient than suppressors, but we have to pay a price for this. The farther back we go in time, the larger the variety of ways to reach each unwanted state of mind. Accordingly, to prevent a particular mental state from occurring, an early-acting censor must learn to recognize all the states of mind that might precede it. Thus, each censor may, in time, require a substantial memory bank. For all we know, each person accumulates millions of censor memories, to avoid the thought-patterns found to be ineffectual or harmful.

Why not move farther back in time, to deflect those undesired actions even earlier? Then intercepting agents could have even larger effects with smaller efforts and, by selecting good paths early enough, we could solve complex problems without making any mistakes at all. Unfortunately, this cannot be accomplished only by using censors. This is because as we extend a censor's range back into time, the amount of inhibitory memory that would be needed (in order to prevent turns in every possible wrong direction) would grow exponentially. To solve a complex problem, it is not enough to know what might go wrong. One also needs some positive plan.

As I mentioned before, it is easier to notice what your mind does than to notice what it doesn't do, and this means that we can't use introspection to perceive the work of these inhibitory agencies. I suspect that this effect has seriously distorted our conceptions of psychology and that once we recognize the importance of censors and other forms of negative recognizers, we'll find that they constitute large portions of our minds.

Sometimes, though, our censors and suppressors must themselves be suppressed. In order to sketch out long-range plans, for example, we must adopt a style of thought that clears the mind of trivia and sets minor obstacles aside. But that could be very hard to do if too many censors remained on the scene; they'd make us shy away from strategies that aren't guaranteed to work, and tear apart our sketchy plans before we can start to accomplish them.